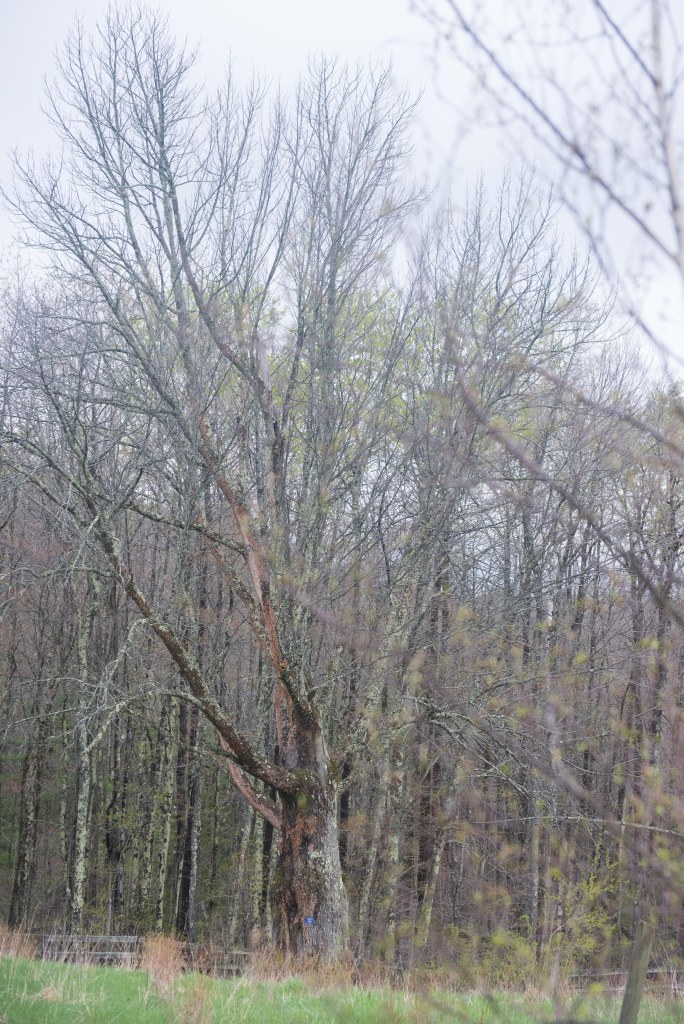

The Bicknell White Ash, summer 2018

Ann Bicknell’s White Ash Tree began its life an estimated three hundred-sixty-odd years ago on what was once known as the Poor Farm, on Old County Road. The tree is surely among, if not THE, oldest residents of our town this wonderful tree has stood at what is now the edge of a field of blueberries on Old County Road. Before the blueberries the field was a horse pasture and before that … this was the Poor Farm that is marked on the 1858 map of Deering. And before that?

The 19th Century Deering Poor Farm from Old County Road

Mark and Ann Bicknell took up residence with this old tree in 2015. She came from an urban life. The farm on Old County Road was the fulfillment of Ann’s dream of a place to have horses. She had found the perfect place. Horses gamboled in the pasture and eyed me suspiciously as I made my (not quite) daily morning walk past them. My first recollection of Ann and Mark was when they brought us Christmas cookies in their horse-drawn sleigh, crossing the fields and open land that separated our two houses.

Mike Margulies, resident on Old County Road since he was a teen in 1954, used to walk along the road each morning too. An outgoing guy, he stopped to talk to the newcomer Mark Bicknell and in the course of their conversation Mike learned that Mark was a Bicknell and that Mike and Mark’s father had worked together as short-order cooks some time earlier. Small world? We call it ‘Deering Magic.” Mike and his wife Bette brought up their family on Old County road, not more than a quarter mile from the Bicknell White Ash. They were the doyennes of our little group.

Mike was a man of many many interests. For nearly forty years he taught 6th through 8th grades in Bennington and Hillsborough until he retired in 2002. He taught model rocketry and hunter safety to kids in town. For several years he kept a sled dog kennel and raced teams around New England. He was a musician, playing bass in local classic rock bands. Mike Margulies was the true Renaissance Gentleman and a great friend.

Not long after Mark and Ann settled in Deering Ann was diagnosed with a brain tumor that would prove fatal. Ann loved her white ash tree. She understood that this very big and very old tree was special, and knowing that I was keeping a list of our town’s biggest trees, urged me to add her tree to the list.

The original Big Tree list for Deering was compiled in 1980 with an update in 1985. I inherited the list, an unruly pile of bits of paper, around 2012 or 2013. Somehow the original compilers of the list missed obvious trees, including this wonderful ash tree. Clearly visible from Old County Road (although I note that Old County Road at that time was unpaved and did not carry as much traffic as it does now that it has been paved), I do not know how nobody included it in the list. Ann was passionate about having this tree recognized.

One Sunday morning in mid March of 2015 a small team set out to measure the tree. Ann and Mark Bicknell, Mike Margulies, neighbor and friend Kay Hartnett, my wife Patty and me. First, we breakfasted on pancakes with maple syrup and coffee in Ann and Marks kitchen, a most convivial affair. Then we put on our snow shoes and crossed the field to the tree, measuring tape in my pocket.

Image on the right, from the left: Kay , Ann, Mark, Patty and Mike

I had not been up close to the tree before this Sunday. The deep gulch of a heart rot hollowed the trunk, but the surrounding sapwood was thick and strong. Strong enough to support the massive branches and spreading canopy. Mike recalled the time when a large branch broke away from the tree, but now despite the heart rot and hollowed trunk, the tree seemed to be doing well.

This beautiful tree was big! It took all of us to bring the measuring tape around the trunk at a height of 4 feet. It appeared to me that this white ash was bigger than any of those that were included in the UNH Big Tree List. My nomination lead to the arrival of an official measuring team of the UNH Big Tree Project. They measured height and canopy spread in addition to the circumference of the trunk and found that it was indeed a big white ash tree!

In 2020, Fraxinus americana Tree Number 1079, the Bicknell White Ash, was named the State Champion White Ash with a height of 81 ft, crown spread of 68 ft, and circumference of 234 inches. Today the tree is recognized as a National Co-champion White Ash Tree, sharing the honor with a tree in Madbury (https://extension.unh.edu/natural-resources/forests-trees/trees/nh-big-trees).

Emerald Ash Borer was first noticed in New Hampshire, in the Concord area, in 2013 and it was first recorded for Deering four years later, in 2017. The effect of the disease is notable around town, with many trees having been removed, but the Bicknell Ash seemed immune. Younger trees surrounding it, maybe its children, looked unhealthy, but this old tree continued to produce a dense dark green canopy of leaves. Until this year.

Infected, 100-year-old ash trees at the Spinner Farm on Old County Road

In March of this year signs of Emerald Ash Borer showed up in our Old County/Hedgehog Mountain Road neighborhood. A row of roughly 100-year-old ash trees at the Spinner Farm, next to the Bicknell Farm, was entirely infected. At the same time the Bicknell’s White Ash tree, which had so far seemed immune, was obviously badly infected. Blonding of the bark, the white flecks of bark the result of woodpeckers pecking away the bark to get to the beetle’s larvae, was visible throughout the sad looking tree.

As the season progressed the canopy of this grant being had only a sparse production of leaves.

Peeling the bark away reveals the serpentine larval feeding galleries. They disrupt the sapwood of the tree, preventing the transport of water from the roots to the crown.

At this point the only thing to do is remove affected trees in the likely vain hope of limiting spread of the beetle.

This might not be the last year for Deering’s own magnificent National co-champion White Ash tree. It might hang on a while longer, producing fewer leaves each year if its new owner, a child of Mark Bicknell, does not have it cut out.

But the death of this champion is only a part of the tragedy of the Bicknell White Ash.

Ann Bicknell did not live to see her White Ash crowned a champion. She knew it was a champion none the less. Her stewardship of this wonderful arboreal companion ended in April of 2015, just short of her 50th birthday. Her husband Mark, a melancholy man, could not adjust to life without Ann. He died in 2022, short of his 60th birthday. Their ashes are placed at the base of the tree. Mike Margulies, a gentleman and a scholar in every good sense, passed away at 80 years in 2020. Good friends all.

We are a small, rural town. A lot of our area is forested. Big trees share the Deering space with us. They provide seed for our forests; they shelter other residents in their broad canopies and in the soil below them. They provide comfort, physical and emotional, for us as needed. They hold the climatic history of our town over centuries in their trunks. They were here long before us. Is Ann’s ash cognizant of us? I don’t know, but I, like Ann, cherish this tree and am saddened by (personal pronoun) passing.

- ABOUT …. EVERYTHING

- BIG TREES IN DEERING

- Fungi & Lichens

- Insects

- INVASIVE PLANTS AND ANIMALS FOUND IN DEERING

- Mushrooms found in Deering

- Picnicking

- Seen in Deering: from around town

- Trails and kayaking in Deering

- Wild Flowers

- Wildflowers in Deering

- ABOUT …. EVERYTHING

- BIG TREES IN DEERING

- Fungi & Lichens

- Insects

- INVASIVE PLANTS AND ANIMALS FOUND IN DEERING

- Mushrooms found in Deering

- Picnicking

- Seen in Deering: from around town

- Trails and kayaking in Deering

- Wild Flowers

- Wildflowers in Deering

Painted Ladies to occur in our area in a lifetime. This past weekend, over a dozen were observed nectaring on zinnias in our flower garden. This phenomena isn’t just happening in Deering, but is being reported throughout New England and elsewhere across the continent. If fact, this year the migration has been large enough to register on the National Weather Service’s radar imagery. I hope you enjoy the flash of orange and black wings in your gardens as we have.

Painted Ladies to occur in our area in a lifetime. This past weekend, over a dozen were observed nectaring on zinnias in our flower garden. This phenomena isn’t just happening in Deering, but is being reported throughout New England and elsewhere across the continent. If fact, this year the migration has been large enough to register on the National Weather Service’s radar imagery. I hope you enjoy the flash of orange and black wings in your gardens as we have.